Know your buckets

A while ago I’ve written a simple tool (Java HashMap Analyser) for hash map analysis and almost completely forgot about it. The whole idea started one day at lunch when a colleague of mine said “you should use a hash map for this, it has O(1) performance”. Oh well… Little did he know how deep the rabbit hole is, so I’ve decided to write a tool for better understanding what’s going on inside a hash map. This post should give you some basic understanding about how a Java hash map handles hash collisions and how Java HashMap Analyser can help you.

A simplified quick reminder of how a hash map works before running our analyser:

- hash map is basically an array of key-value pairs which are stored into buckets

- bucket is a linked list or a balanced tree, depending on its size

- each key is hashed using its hash code and “adjusted” to fit into the current hash map size

- hash collisions are handled by storing all values with the same hash into the same bucket

- you can usually find average time complexity O(1) and O(n) as worst when dealing with hash tables

Simple as that and good enough for now.

Let’s try with a simple example and see how can this tool help us understand what’s going on inside the hash map.

HashMap<String, Integer> map = new HashMap<>();

map.put("a", 1);

map.put("ab", 2);

HashMapAnalyser<String, Integer> analyser = new HashMapAnalyser<>(String.class, Integer.class);

analyser.analyse(map);

This code will output:

HashMapMetadata{

totalBucketsCount=16,

usedBucketsCount=1,

bucketsMetadata=[

BucketMetadata{

bucketIndex=1,

nodeType=LINKED_LIST_NODE,

nodesData=[

NodeData{key=a, value=1, hashCode=97},

NodeData{key=ab, value=2, hashCode=3105}

]}]}

Giving us info about:

- underlying hash table size

- used buckets and indexes

- data stored in buckets with hash

- type of buckets (before conversion) - linked nodes or self-balanced red black binary search tree

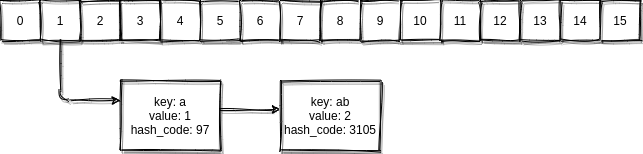

Using this data we can conclude that our map should look like this:

Let’s break it down:

totalBucketsCount=16

This is the default value for initial bucket count. You’ll find a lot of values that must be a “power of two” in hash map implementation; it’s due to simplicity and performance improvements.

usedBucketsCount=1

BucketMetadata{

bucketIndex=1,

nodeType=LINKED_LIST_NODE,

nodesData=[

NodeData{key=a, value=1, hashCode=97},

NodeData{key=ab, value=2, hashCode=3105}

]}

It means our keys “a” and “ab” with hash code 97 and 3105 are located in the same bucket at index 1 which is of type linked list. It’s not the standard linked list you’ll find in java.util package, but a much simpler singly linked list which doesn’t implement the List interface.

So we have a map with only two keys, and they’re both in the same bucket although they clearly have different hash code, value and key.

Ideally this kind of collision should not happen or at least with on only 2 different keys… but it did.

We probably got something wrong. (That’s always my first thought.)

Let’s investigate our hash collision:

When we open HashMap::put we can see the first thing that happens is key hashing:

static final int hash(Object key) {

int h;

return (key == null) ? 0 : (h = key.hashCode()) ^ (h >>> 16);

}

For our two keys “a” and “ab” evaluated in REPL, it yields:

"a" => "a".hashCode() ^ ( "a".hashCode() >>> 16) => 97"ab" => "ab".hashCode() ^ ( "ab".hashCode() >>> 16) => 3105

So far so good, our hash code is the same as our analyser reported.

Let’s try to see what’s next in HashMap::putVal:

final V putVal(int hash, K key, V value, boolean onlyIfAbsent,

boolean evict) {

Node<K,V>[] tab; Node<K,V> p; int n, i;

if ((tab = table) == null || (n = tab.length) == 0)

n = (tab = resize()).length;

if ((p = tab[i = (n - 1) & hash]) == null)

tab[i] = newNode(hash, key, value, null);

else {

Node<K,V> e; K k;

if (p.hash == hash &&

((k = p.key) == key || (key != null && key.equals(k))))

e = p;

else if (p instanceof TreeNode)

e = ((TreeNode<K,V>)p).putTreeVal(this, tab, hash, key, value);

else {

for (int binCount = 0; ; ++binCount) {

if ((e = p.next) == null) {

p.next = newNode(hash, key, value, null);

if (binCount >= TREEIFY_THRESHOLD - 1) // -1 for 1st

treeifyBin(tab, hash);

break;

}

if (e.hash == hash &&

((k = e.key) == key || (key != null && key.equals(k))))

break;

p = e;

}

}

On the first insertion our table will be uninitialized and resize() method will initialize it using defaults with 16 buckets and 0.75 load factor.

Once initialized finding the right bucket happens here: (n - 1) & hash

For our two hash codes evaluated in REPL, it yields:

"a" => (16 - 1) & 97 => 1"ab" => (16 - 1) & 3105 => 1

The (n - 1) part is because n is a power of two and any (n - 1) will have all bits set.

It’s a property of power of 2 numbers which can be used for faster modulo operations by using bitwise &;

it’s the same as writing hash % n.

It’s hard to put into perspective the result of a bitwise & between two numbers without looking at binary values. Here’s the same code just in binary:

"a" => 0001111 & 1100001 => 0000001"ab" => 000000001111 & 110000100001 => 000000000001

So looks like our analyser was right after all: both keys belong into the same bucket with index 1.

There is a lot more in putVal we haven’t mentioned; the code is somewhat hard to read because of checks if value should be replaced and if the bucket should be converted from a linked list to a balanced tree and vice versa.

In my opinion that’s a lot of complexity for questionable performance improvements, probably the benefits of it can be seen only on large buckets with more reads than writes. Insertion in balanced tree could take more time than linear search over linked list, which again is a bad performing data structure for linear search because it doesn’t take advantage of any CPU cache optimizations such as locality of reference… But that is a topic for another post.

Regarding Java HashMap Analyser implementation, it uses reflection to read hash map internals. When analysing buckets all data is converted into an ArrayList, more cache friendly structure than linked list or tree, so you can have better performance while iterating over all values while preserving the original bucket type (nodeType).

Conclusion

We have explored how and why a hash collision can(will) happen. The only way to minimize this, since collisions are almost inevitable, is to provide a good hash code and tune map initial size and load factor. If you’re interested in how data is being distributed among buckets, Java HashMap Analyser can help you check under the hood of a HashMap, providing info about usage and structure types.